One of the cornerstones of the ISC's approach to Shakespeare is the way we try to immerse our audiences in the world of the play. We stage our productions so that the action surrounds and envelops the viewers, and characters can be seen behaving "in character" even when they're "offstage."

For this summer's production of Macbeth, we plan to take this approach even further. When the audience enters the performance site, we want them to feel like they're stepping back in time, into another world...a world of kings and queens, warlords and witches, soldiers and servants.

To do this, we'll be creating several distinct environments within the performance site, each active and populated throughout the performance. Audience members will be able to walk through these areas before the show and see the characters going about their business. We want to create the feeling that this is a world where these characters live all the time, and the scenes of the play are just brief episodes in their lives that we happen to be focusing on for a short time. A sort of "living-history-meets-Shakespeare" approach.

One of these environments will be the witches' grove. You can see more about our approach to the witches on the Witches page.

Another key setting in the play is Macbeth's castle and its environs. There are few images more evocative and intriguing than a ruined Scottish castle:

So we wanted to incorporate this idea of a crumbling castle into our set design for the show, with the castle being one of the "live" environments, like the witches' camp...a world in which servants bustle and clean, people come and go, and life goes on even when it's not the focus of what's happening onstage. We're also aware of the need to make our actors more visible to everyone watching the show — especially those in the back. So for the first time, we'll be putting up a raised stage for this production. Finally, we wanted the set design to reflect some of the key patterns of imagery in the play, among which blood and serpents are very important.

Set designer J.G. Hertzler, the director and designer of last year's production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, brought all of these elements together in a preliminary concept sketch for the Macbeth set, which you can see below. There's a ruined castle arch, a raised stage, blood-colored banners with Celtic snake symbols painted on them, and a walkway that extends out into the audience area. The set will be the focal point of the performance and ensure that everyone has a good view of the action — although, as always, we'll be making use of the entire site in one way or another.

We think it's going to be pretty exciting...

Costuming will also play a crucial role in our effort to fully immerse the audience in the world of the play. Our costumes will be designed to evoke the world of early Medieval Scotland in which these characters lived.

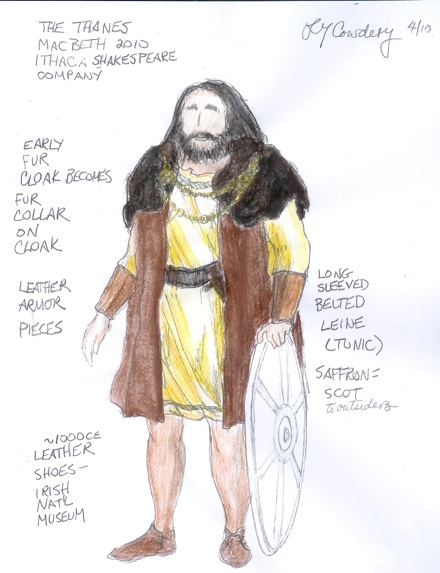

As ISC costume designer Lauren Cowdery says:

"We'd like the costumes to be influenced by whatever is known about Scots clothing around 1000 CE. There are few records, and all of them are verbal — telling us that cloth was generally dark, for example, and that warriors were bare-legged.

Irishmen and Scots traveling in foreign countries were stereotyped not by plaid clothing (tartans began after Shakespeare died) but by saffron-colored tunic/shirts, called leines. That dye was mightily expensive, and only the rich used it — not surprising that it was the fashion choice of ambassadors or those with the means to travel abroad.

Beyond that, we suppose that cloaks that once were all fur or all cloth become fur-collared cloth by the time they appear in images after 1300. Clothing historians are still puzzling out how cloaks were worn, but the most rational suggest that bulky cloaks were shed for battle, however they may have been festooned for day wear."

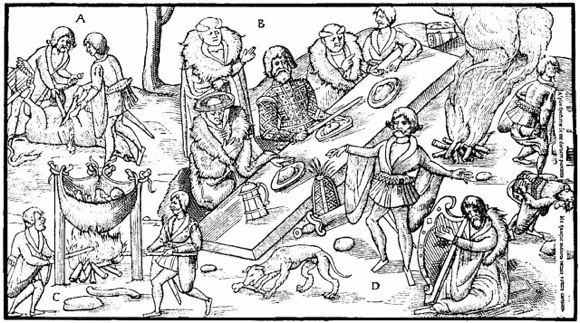

The image above shows an early conceptual sketch for one of the thanes in the play, based on this research. And below is a drawing from much later, 1578, of a Scottish clan chief being entertained at dinner — by a bard, a harpist, and, apparently, two men mooning him:

These and many other bits of historical research provide the raw material for costume ideas, which must then be filtered through the artistic sensibility of the designer and director — and, of course, adjusted to the pragmatic needs of actors in an outdoor theatre setting.