Twelfth Night was an important date in Shakespeare's England, the night of the twelfth day after Christmas and the last day of the traditional Christmas holiday period. As such, it was generally celebrated with plenty of revelry, feasting and drinking, misrule, and, often, the performance of plays at Court. The attitude was something like: "Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we go back to work."

There's not much in the play that suggests a direct connection to the Twelfth Night holiday — other than one little snippet of a song — but the portrayal of revelry and misrule in many scenes certainly reflect this general feeling to some extent.

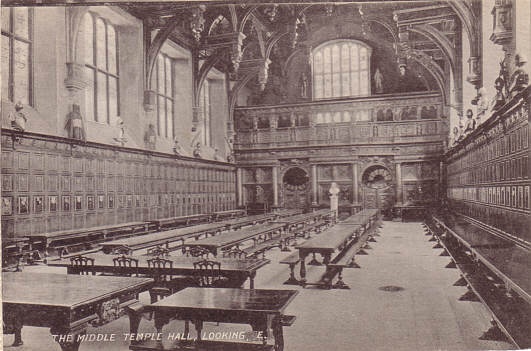

It's rarely possible to know exactly when Shakespeare wrote any of his plays, but Twelfth Night appears to have been the last of Shakespeare's major romantic comedies to be written. Its first known performance was in 1602 and occurred not at the Globe but in the hall of the Middle Temple, one of the Inns of Court where lawyers were trained in Shakespeare's London. They often invited acting companies to perform as part of their holiday celebrations, and one student's record of this performance of Shakespeare's play has survived. The hall is just a big open room filled with dining tables, as can be seen here:

No one can say for sure exactly how Shakespeare's company would have set up their performance in the space — perhaps at one end, perhaps in the middle with the tables cleared away.

The time of composition is significant because this was the time of a major shift in direction in Shakespeare's writing career. Prior to this, the majority of his plays had been romantic comedies (A Midsummer Night's Dream, As You Like It, Much Ado About Nothing, etc.) and history plays, with a few isolated tragedies thrown in. But somewhere in the vicinity of 1600-1602, he shifted his focus and began the sequence of great tragedies that dominated his output for the next decade or so: Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and so on. The comedies he wrote after this time have a very different tone and feel from the earlier ones — more cynical, more satirical, less romantic. Twelfth Night seems to have been written right around this turning point in Shakespeare's career. As such, it's the last of its kind, a romantic comedy written by a playwright who was about to turn away from romantic comedy toward darker genres. It might be said to be the greatest, funniest, and most perfect of the romantic comedies, written by a playwright at the very top of his game. But it also contains some surprisingly dark material, especially near the end, mixed in with the comedy and romance, hinting at the turn toward more serious subjects and greater realism that was soon to come.

This sense of Shakespeare both perfecting his technique in the genre of romantic comedy and looking beyond it to the major tragedies has been important to us as we worked on this production. We wanted to do our best to do justice to the full range of tones, moods, and emotions that Shakespeare has packed in here. Twelfth Night offers an amazingly rich and layered emotional experience to an audience, from some of the flat-out funniest comedy Shakespeare ever wrote to some shockingly dark and angry moments. We didn't want to reduce all of this richness to something one-dimensional — to smooth over the serious parts because "this is supposed to be a comedy," for example. Instead, our goal was to emphasize the wide range of tone and feeling we saw in the play as much as possible.

Twelfth Night is a romantic play — it's full of characters falling in love — but for us it's also a Romantic play, in the broader sense of that word. Shakespeare's Illyria is a land of shipwrecks and pirates, twins separated and reunited, and noble characters expressing their deep passions in beautiful love poetry. It's a world where everything is just a little larger than life, a little beyond our everyday experience — a world of which any true Romantic might approve.

It's also a world of imagination. The importance of the imagination was a major component of the Romantic movement in art and literature, but, as with most things, Shakespeare got there first. "Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind," he tells us in A Midsummer Night's Dream, and that idea informs almost all of the romantic relationships in Twelfth Night. Few if any characters who fall in love in this play are really seeing the object of their affections clearly. They all see what they want to see and project their own fantasies, wishes, and self-deceptions onto the others. Malvolio's romantic fantasy is the most overt, but Orsino and Olivia both create elaborate romantic fantasies of their own and end up falling in love with characters who "are not what they are" — or at least, are not who they think they are. The powerful influence of the imagination on our perceptions of reality is what makes all the tricks and disguises in the story of the play possible.

That idea extends to the members of the theatre audience as well, since a willing imagination is also the source of the suspension of disbelief that makes all theatre possible. And since the audience is in on all the tricks being played and the disguises being used, they become co-conspirators with the characters in all their shenanigans — which can become somewhat uncomfortable when at least one joke goes too far.

In keeping with the importance of this general theme of Romanticism, we have chosen to evoke a vaguely 19th-century feel with many of the design elements of this production — the items of shipwreck debris, the costumes, and some of the music.

The various love triangles and romantic entanglements of Twelfth Night are only part of the play, and not necessarily the most memorable part. Twelfth Night also anticipates the classic British "above-stairs, below-stairs" comedy structure, in which the interactions of the noble, aristocratic, upper-class, "above-stairs" characters are counterpointed against the goings-on among the "below-stairs" servants and staff — i.e., the help. So while Olivia, Orsino, and Viola are caught up in their love triangles, a second plotline involving the members of Olivia's household unfolds. "The help" in this case includes Olivia's steward, Malvolio, the head of her household staff; her gentlewoman attendant, Maria; her household jester, Feste; and Fabian, whose exact position is never specified. They're joined by Olivia's drunken uncle Sir Toby Belch and his foolish friend, Sir Andrew Aguecheek, both of whom should technically be part of the "upstairs" world, by virtue of their social rank, but who seem much more at home hanging out with the help and having fun.

This comic subplot has a rougher and slightly more realistic feel than the romance-driven main plot, and it may be the part of the play that people remember most. That was certainly the case for the Elizabethan law student who described the first recorded performance of the play — he didn't mention the romances at all, but he was very enthusiastic about the trick played on Malvolio by Sir Toby and the rest. All the earliest references to the play, in fact, focus on the gulling of Malvolio as its central and most striking feature. In records of Court performances, the play was actually referred to as Malvolio, and King Charles I made a note in his copy of Shakespeare's works indicating that Malvolio was the character that stood out to him.

In the play, Antonio is a male character. He is the sailor who rescues Sebastian from the shipwreck and follows him to Orsino's court, where he is arrested for having fought against Orsino in a naval battle some time ago. (Whether he is or isn't a pirate appears to depend on whom you ask — Orsino says he is, Antonio says he isn't.)

The relationship between Sebastian and Antonio has been viewed in many different ways, but it is unquestionably an intense one. The language they use toward one another and the extent of Antonio's devotion to Sebastian suggest that their relationship goes beyond friendship, which adds another dimension to the variety of romantic attractions in the play. In a play where a man and a woman both fall in love with a woman disguised as a man — a situation complicated even further by the fact that all the female characters would have been played by boys in Shakespeare's time — gender and sexuality are more fluid than fixed, and a homoerotic attraction between Sebastian and Antonio seems perfectly in keeping with the play's exploration of many different permutations of love and desire.

In our production, however, Antonio has become Antonia and is played by a female actor. We know that some people will like this choice and others won't. We see both sides of the issue: on the one hand, we lose one aspect of the fluid play with gender and sexuality that is so much a part of this play. On the other, we gain another great female role, of which there are rarely enough in Shakespeare's plays. In the end, this was the choice that worked best for us for this production, and we trust that the heart of the play remains intact. And, of course, we think having a female pirate is always a good idea...

Bears and bear-baiting are referred to frequently in the play, and this has been another important aspect of our approach to this production.

Bear-baiting was a cruel and violent Elizabethan sport in which a bear was chained to a stake and then "baited" — taunted and attacked — by dogs. As uncomfortable as it may be for us to consider, this activity was closely linked to the theatres of Shakespeare's time. Theatre and bear-baiting were included in the same basic class of popular entertainments, with theatres and bear-baiting arenas often located right next to one another or used interchangeably for both activities. And the famous design of the outdoor Elizabethan theatres like the Globe may even have been based on the very similar design of the bear-baiting arenas.

In the play, a number of characters compare Malvolio to the bear being baited, and we have taken this metaphor seriously in the later stages of the trick that is played on him. Our staging of Act 4, Scene 2 is intended to evoke the general set-up of a bear-baiting, as shown in images like this one:

If Malvolio is the bear, then those who attack him are the dogs, and his last line in the play refers accordingly to "the whole pack of you." Exactly who he includes in this "pack" is not clear — it might be just the characters who played the trick on him, or the entire cast, or perhaps it extends to the audience as well, since we become part of the "pack" that laughs at him earlier in the play.