Henry IV: Banish All The World

A Midsummer Night's Dream

July 9-26, 2015

at Cornell Plantations

Tickets on sale now!

ISC's 2015 summer season features the second production in our epic series of Shakespeare's history plays, along with the ever-fresh, ever-funny modern favorite, A Midsummer Night's Dream.

See the shows for free!

Ushers still needed at many performances

Who's Who In Henry IV

One of the difficulties modern audiences have with Shakespeare's history plays is that there are so many characters, and it can be difficult to keep straight who they are and what they're fighting for. So here's a quick guide to the major characters in Henry IV. As with Richard II, we'll be starting Henry IV with a brief prologue that will give you a visual introduction to the main characters and provide the necessary context for the story.

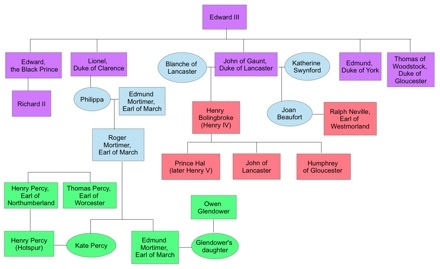

The following chart shows the main characters in Henry IV and their family relationships:

Henry IV and his family and key supporters are shown in red, while the key members of the rebel coalition are in green. The previous generation of the royal family is shown in purple; although they do not appear in this play, they are referred to often and the conflicts and relationships of the current generations trace back to them. Individuals in blue boxes do not appear in the play but are important as connectors of the key characters.

Each of the leaders of the rebels have their own motives for fighting against Henry IV, motives which are strengthened by their family connections and, in most cases, arise out of the events depicted in Richard II:

- Northumberland, his son Hotspur, and his brother Worcester helped Henry Bolingbroke take the crown from Richard II, but seem to feel in this play that Henry has overstepped his bounds, has not shown them enough respect, and has not rewarded them adequately for their help — a development that was predicted with keen insight by Richard II shortly before his death in the previous play.

- Hotspur is related by marriage to Edmund Mortimer — who was declared the official heir to the throne by Richard II and claims descent from the second son of Edward III, as opposed to Henry IV's descent from the third son. Mortimer, therefore, arguably had a stronger claim to the throne than Henry did. (This fact will take on ever-greater importance in later plays in the history series, especially the Henry VI plays.) Mortimer's claim to the throne provides a rallying cry for Hotspur and his family as they seek redress for their grievances against Henry IV.

- Owen Glendower was a Welsh nobleman who was fighting for independence for Wales from English rule. When he captured Edmund Mortimer, Mortimer married Glendower's daughter, thereby joining their causes.

- The Earl of Douglas, not shown in the chart, was a Scottish clan leader fighting for independence for Scotland from English rule. When he was captured by Hotspur, they recognized each other as kindred spirits with a common enemy, and joined forces against Henry IV.

- Another group of rebels, also not shown in the chart, is led by the Archbishop of York. The Archbishop was a powerful religious and political leader whose brother was the Earl of Wiltshire — one of Richard II's close companions who was executed without trial by Henry Bolingbroke when he was in the process of taking over the country. (This is a minor historical mistake; the Archbishop and the Earl of Wiltshire were actually cousins, not brothers.)

- Another key member of the Archbishop's faction is Thomas Mowbray — the son of the Thomas Mowbray who was banished by Richard II and died in exile after being accused of treason by...Henry Bolingbroke.

In almost every case, the rebels' motivations are a response either to Henry's own actions or that of the English monarchs more generally, in their attempts to maintain dominion over Scotland and Wales. This is one of the most profound elements of Shakespeare's plays in general and his history series in particular: he shows us not only the characters' actions but also the consequences of those actions as the story unfolds. And we see here how tightly interconnected the history plays are: Henry's actions in Richard II are what generate most of the conflicts in Henry IV.

There is actually a significant historical mistake in Shakespeare's play: the Edmund Mortimer who was Hotspur's brother-in-law and married Glendower's daughter was not the same Edmund Mortimer who was declared heir to the throne by Richard II. Shakespeare's primary historical source, Holinshed's Chronicles, conflated these two different Edmund Mortimers into a single individual, and Shakespeare followed suit in his plays. Although this is a historical error, it undoubtedly makes for a better story — having a single Edmund Mortimer who has a claim to the throne and is connected by marriage to several members of the rebel coalition clarifies the motives of the rebels and raises the stakes in their conflict with Henry. Our family tree diagram and these notes reflect the relationships as they are portrayed in Shakespeare's play, rather than as they were in historical fact.

Hal And His Fathers

Although the Henry IV plays are titled after the reigning monarch, Henry is not the central protagonist of the story. That place belongs to his son Prince Hal, the heir to the throne, who will go on to become King Henry V in the next play. The Henry IV plays are largely focused on the progression of Hal's relationships with each of the two major father-figures in his life.

First, there is his real father, the stern, authoritative King, who expresses constant disapproval of Hal and openly wishes that Hotspur was his son instead. The extent to which Hal has been wounded by his father's comments is made clear at one of the key turning points in the play, when Hal vows that "this gallant Hotspur, this all-praised knight, and your unthought-of Harry" — i.e., Hal — will meet in battle, and Hal will prove to his father that "I am your son." This moment is the first step in the long reconciliation process that will bring the two characters together in the end, as Hal prepares to take his place as the next king.

And then there is Falstaff, the lovable rogue who steals purses, drinks sack, and hurls insults back and forth with Hal. Hal's relationship with Falstaff provides all the joy, warmth, camaraderie, affection, and acceptance that is lacking in his relationship with his real father. Falstaff and the tavern crew function like a big, loud, unruly family; they squabble and play tricks on each other, but underneath all that they are fiercely devoted to each other and always have each others' backs when it really matters. The scenes between Falstaff and Hal are boisterous and hilarious, but they are also the emotional heart of the play — which makes the final encounter between the two of them all the more heartbreaking. For just as Hal must reconcile with his father before taking the throne himself, he must also recognize that there is no place for his carefree revels with Falstaff in the world of a king.

Tickets on sale now!

And of course we don't want to forget the most perfect theatrical comedy ever written, playing this summer in rotation with Henry IV.

Quarreling lovers, feuding fairies, a mischievous hobgoblin, and a hapless band of wanna-be actors come together in the forest, with hilarious results...

The Ithaca Shakespeare Company · Ithaca, NY 14850 · info@ithacashakespeare.org